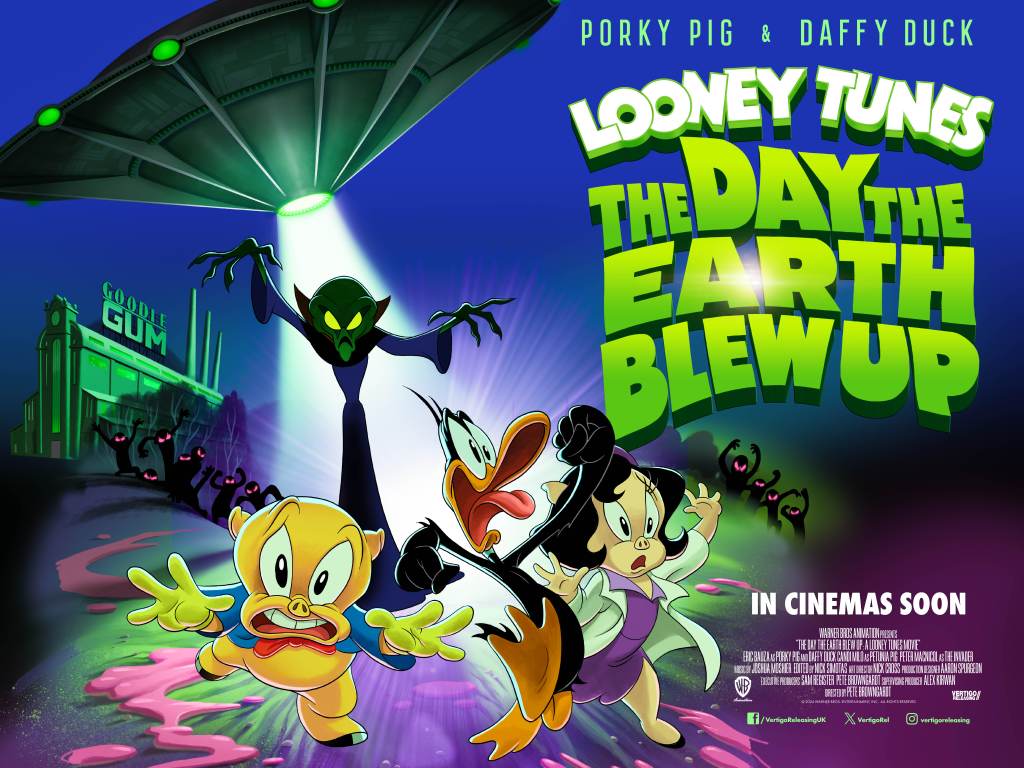

This animation from the Looney Tunes team features Daffy Duck and Porky Pig on a mission to save the world from alien invasion. In UK & Irish cinemas from 13th February 2026.

The tone is set as a scientist at an astrological observatory is alerted to an advancing asteroid heading directly towards earth along with a UFO that hurtles down and crash lands with an otherworldly glow, which is the cue for the eerie sci-fi music and the starting credits to roll.

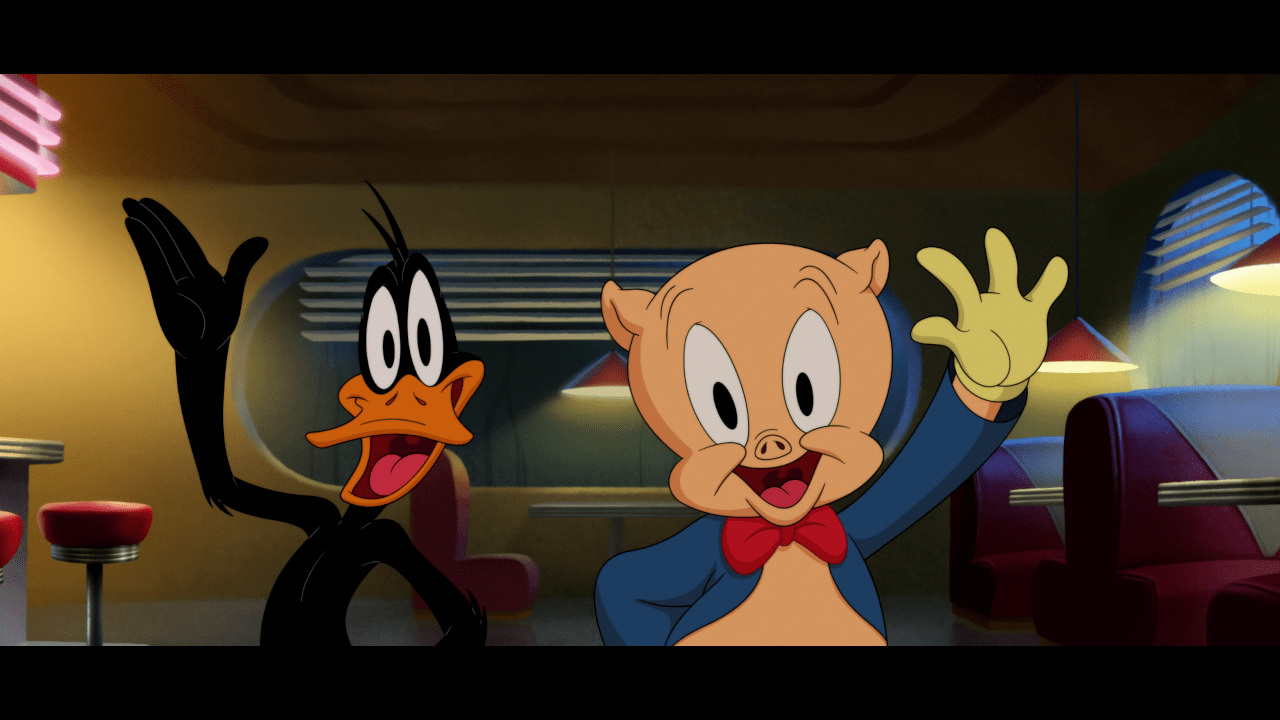

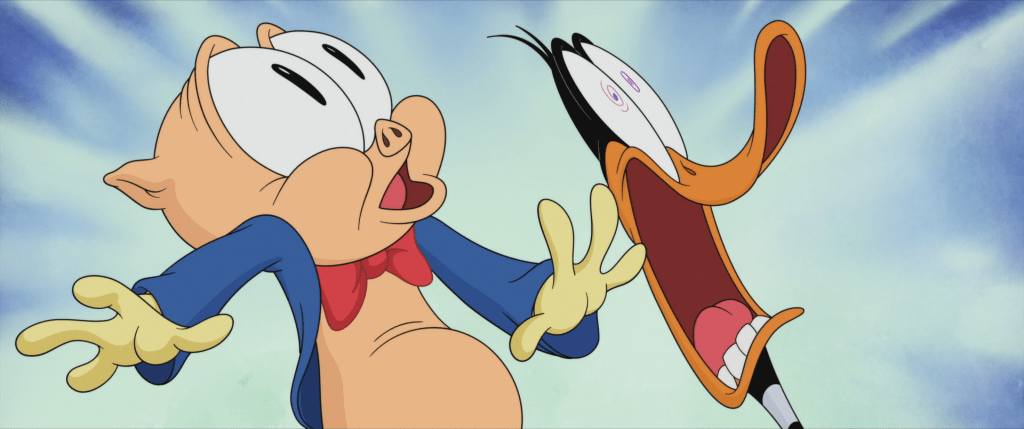

The credits are a cartoon scrapbook look back at the origins of the two Looney Tunes characters Daffy Duck and Porky Pig and how they became best friends growing up on a farm under the protective eye of farmer Jim, and when farmer Jim moves on to the big field in the sky he hands over ownership of the farm house to a now fully fledged Daffy and Porky.

Porky wakes up to see it’s the Annual Home Standards Review inspection and so the two are forced into action to make sure the house passes mustard. Everything seems to be going well in its Looney Tunes way until the hostile inspector points out one small oversight…half the roof is missing from the UFO crash and without a fixed roof they will be evicted!

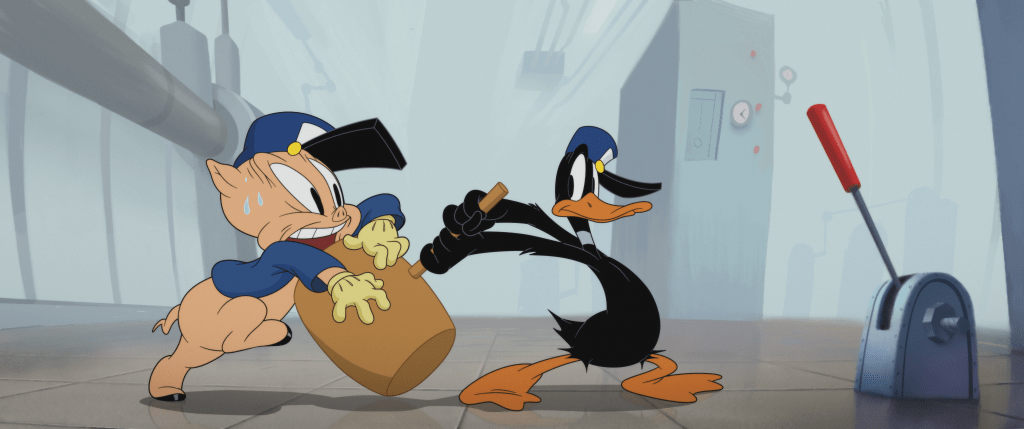

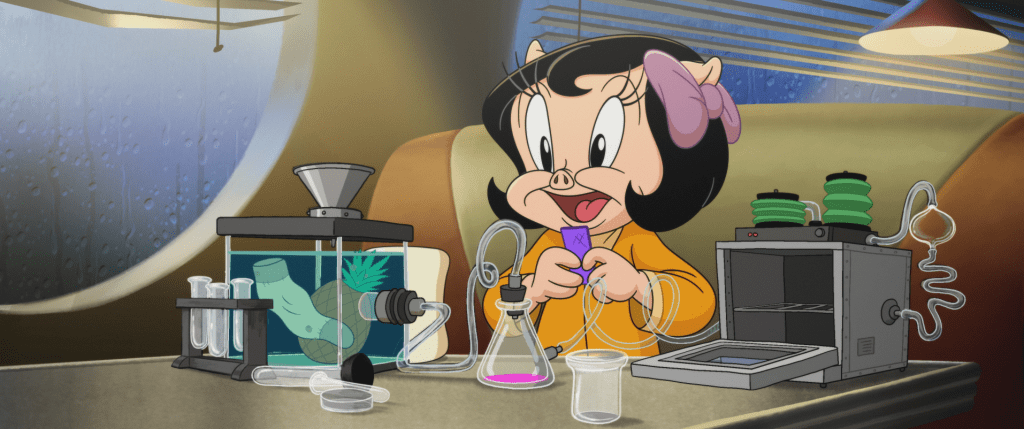

Daffy and Porky need to find work to afford the roof repairs and they try every job they can but can’t hold one down for more than five minutes without (usually Daffy) causing some kind of mayhem getting them fired. This is until they meet Petunia Pig in a cafe who tells them about a job at her bubble gum factory Goodie Gum where she is the flavour scientist.

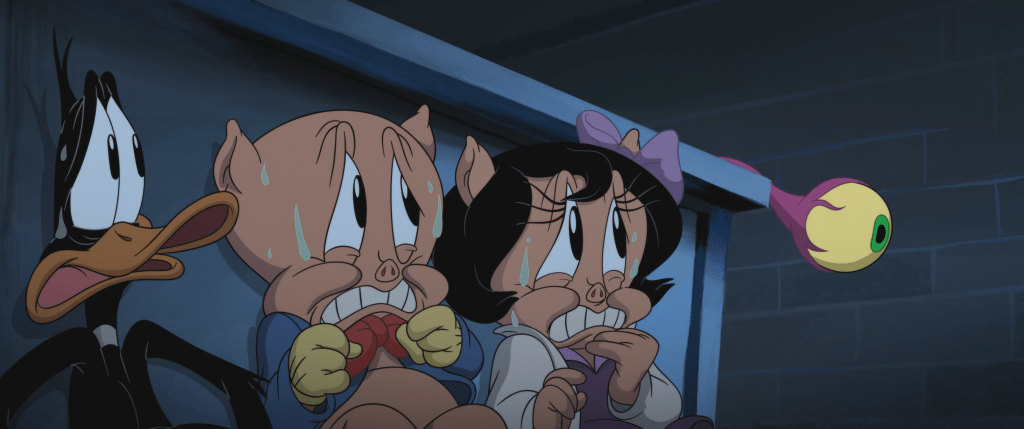

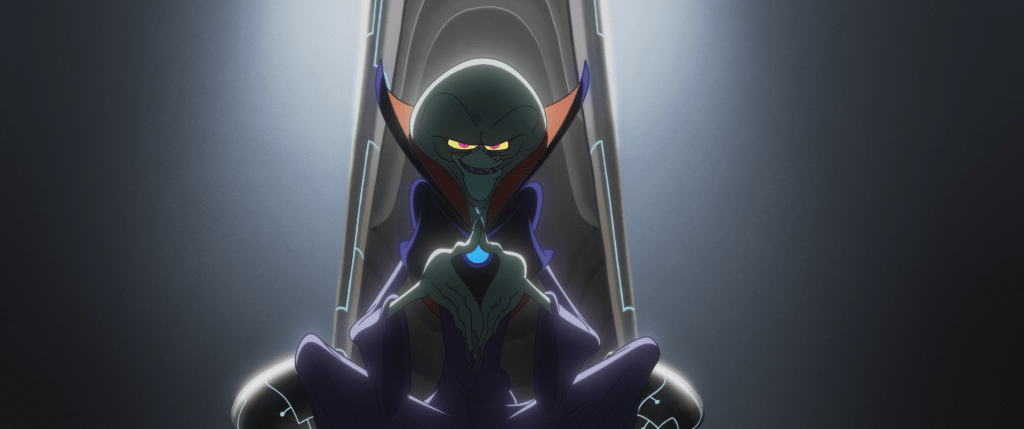

The job couldn’t be simpler and all Daffy and Porky have to do is not screw it up. Of course strange things are afoot and despite Daffy’s propensity for disaster he’s on to something, discovering a trail of the ectoplasm goo that is identical to what they found on their roof. He begins to investigate and uncovers the plot of the alien invaders to tamper with the bubble gum ingredients in order to zombify the human race. Can the duo save the day and will Porky Pig woo Petunia Pig or will Daffy bring about total disaster?

Directed by Peter Browngardt, the simplicity and familiarity bring a warm nostalgia to be shared with all the family but not without complete anarchy ensuing. The potentially grown up themes of house upkeep, finding a job and an alien conspiracy are stripped Daffy Duck and Porky Pig bare with Daffy’s OTT remonstrations and a stuttering pig that still manages to pass the equality sensors. Despite or because of all the lunacy you leave the film with an ectoplasm glow and some grown up moral lessons to ponder.

Find your nearest cinema at: https://www.vertigoreleasing.com/movie/the-day-the-earth-blew-up-a-looney-tunes-movie

Film: Looney Tunes, The Day the Earth Blew Up

Director: Peter Browngardt

Genre: Animation, Comedy, Adventure, Farce, Sci-fi, Alien Invasion

Stars: Eric Bauza, Candi Milo, Peter MacNicol

Run time: 1hr 31mins

Rated: PG