Director Mark Jenkin and producer Denzil Monk talk to the Language of Film about their latest feature film, ‘Rose of Nevada’ appearing at this year’s 69th BFI London Film Festival 2025. In UK cinemas from 2026.

Please introduce yourselves and your film.

MJ: My name is Mark Jenkin, I’m the writer and director of Rose of Nevada.

DM: My name is Denzil Monk, I’m the producer of Rose of Nevada.

Could you give us a quick synopsis of your film?

MJ: Yes, Rose of Nevada is a story about a fishing boat that arrives back in a derelict harbour 30 years after being lost at sea with all the crew lost. Not everybody in the village is entirely surprised by the return of the fishing boat and they take it as a good omen that the boat has returned and decide to put it back into service and they put a new crew onto the boat who are unaware of the history of the boat who then go out and have a fantastically successful fishing trip and then when they return they’ve slipped back in time 30 years and the community mistake them for the original crew that had been drowned.

On IMDB it is described as a sci-fi, fantasy, drama, horror…what can we expect from the film?

MJ:…Musical. We tried not to really define what it was in terms of genre. I mean obviously it’s a time travel film but whether that’s a genre or whether that is a sub-genre and I think what’s happened is once you put the film out there people write about it and then understand really what the film is. So very early on people described it as a sci-fi and I thought it’s not a sci-fi because my idea of what a sci-fi is isn’t this but a time travel film I suppose is a sub-genre of science fiction.

So yeah it’s, I don’t know, I don’t think it’s up to me or us to sort of define what it is. I think certainly on IMDB they’re not categorisations that have come from us. They’re probably from people who’ve written about the film, which is great, that’s one of the most exciting things is hearing what people think the film is and I always joke that when people list off all of these genres I always say and it’s a musical as a joke but actually the other day I realised that it has got a song. It’s as much a musical as a sci-fi I think.

DM: Yep, nothing else to add to that.

MJ: I thought you’re going to sing.

DM: I’m going to agree that it is definitely a musical.

What made you think you could make this film?

MJ: I think I’ve always made films and I’ve always wanted to make films and I’ve always made films in unusual ways. I think when I met Denzil and started working with Denzil he’s got the same sort of optimistic belligerence that I have that the more people tell you not to do something the more you want to do it and sometimes you don’t even need somebody to tell you that it’s not the way to do it. You almost feel it inside yourself and you go well this seems like a crazy thing to do but that might be just the perfect reason to do it.

So this is our most ambitious, expansive film so far and I think certainly for me, and I’m quite comfortable talking for Denzil at times as well because we share a lot of attitudes and opinions. I think we were both excited by the bigger canvas, working within genre, a bigger production, a bigger budget, higher profile stars. I just think that was very exciting for both of us.

DM: Yeah absolutely and it comes with all sorts of unique and interesting challenges but those challenges are the things which give you an edge to sharpen your tools against and that is what’s exciting about filmmaking is, no matter how clearly you think you’ve got it planned out there’s always going to be things that come up, day in day out and that keeps you feeling alive.

MJ: I think we probably both share a little bit of the inability to imagine it’s not going to work during the making of it and actually it wasn’t until Venice and the world premiere when we screened it and it was well received and the critics received the film well, then I allow myself a little moment where I go, thank God, because we could have really screwed this up, but I think both of us don’t entertain those thoughts while we’re making it.

What is your process from script to screen?

Well I write, I kind of write my own scripts but that’s not to say I don’t collaborate. Denzil is the creative producer, also the kind of de facto script editor who I sort of trust implicitly with his feedback and his thoughts and his ideas. Also this one, the story originated from an idea that myself and my partner, Mary Woodvine, who’s also in the film had. The process, in some ways we’re really conventional in terms of the way we make a film. We have a camera, we have a cast, we have locations, we shoot out of order. We’re quite conventional in that way but within there, there’s some very unconventional ways of working. We don’t record any location sounds because we’re always shooting on 16mm film on a clockwork camera that you can’t record sound with so everything’s post synced. I shoot the film myself, I edit, do the sound design and create the score but all with key collaborators. In some ways it’s quite conventional, in other ways it’s unconventional.

How did you manage to get George MacKay as the lead role in the film?

I was introduced to George via the casting director Shaheen Baig and I met George at Shaheen’s office. Obviously I knew about him because he’s been on the screen from when he was about 8 years old in his first movie. I’ve always really loved George. He’s a bit of a chameleon, he never does the same performance twice. He seems to work with interesting directors, he wants to challenge himself. He’s not on a specific career path, he kind of weaves all over the place. When I met him I was thinking of him to play the role that Callum Turner ended up playing, but as soon as I met him and looked into his eyes I thought actually he’s going to be right for Nick, the protagonist of the film.

We just got on very well to start with. I never get actors to read scenes from the film or audition people in a conventional way like that. I just sit down and see whether we get on and whether there’s a shared vision. Very quickly my gut was, I want to cast George in the lead. Like I say, he’d originally come in to meet for Callum’s role. I think we went back and had to say, we don’t want you for that role, we want you for this role. Luckily he’d read the script and he’d read both characters obviously and he was as keen to work with us as we were with him.

What were the major challenges to filming?

A lot of it is outside, which has its own challenges. Shooting at sea is incredibly difficult, which is why we didn’t shoot a whole lot at sea. In the film where we’re clearly at sea, we obviously shot at sea. The other bits where it looks like we’re at sea was a bit of smoke and mirrors. We shot in a studio, we built a studio from scratch in Cornwall and we did a lot of the interiors of the boat, for example, in the studio. We don’t do any sort of trickery, there’s no CGI, there’s no backgrounds added in, there’s none of that. So everything you see on the screen is what was there. We work in a quite old-fashioned way in that way. But for me the challenges are the same as they always are, you know. It’s trying to capture lightning in a bottle and you’re never quite sure whether you’ve captured it or not until you get in the post-production.

But I think, Denzil, you can probably speak more about what the challenges were.

DM: Yeah, I mean the production challenges were definitely significantly greater, although on the previous film, Enys Men, we were shooting with a tiny crew during lockdown, so that came with its own Covid challenges. But this one, there were some really big set pieces that we kind of had to work out how we were going to approach those and how we were going to make those work. But the result of it is there on the screen and you don’t watch it thinking about the three different places where that little sequence was shot and pieced together. You watch it, even on a really early cut, you watch it and you’re totally buying into the reality of the world that’s there. So, yeah, like I said before, all of those challenges are just kind of an exciting thing to get our heads around and work out solutions to. It’s all just like impossible things that you find solutions to. That’s what filmmaking is, isn’t it?

MJ: And I think the difference with Denzil, Denzil will have noticed the big step up in scale because he’s looking at the whole thing at all times, kind of stood back, looking at the beginning and the end of production and everything that comes in between. Whereas with me, even down to the way I shoot, all I’m thinking about is the next few seconds of what we’re shooting and sometimes it’s stressful because I know that we’re doing something and something maybe not in place or something has fallen through or something like that. But really it’s the same process for me each time. I look through the viewfinder and go, well, what are we shooting now? And I shoot it and then I worry about what’s next after that. So for me, it didn’t feel very much different.

DM: There’s kind of like a paradox that happens there as well, isn’t there? Because you’ve written it, because the story is there inside your head and you’re shooting it and you’re also going to edit it and you’re going to shoot it for the edit. There’s such a depth of understanding of the way that the whole thing pieces together that you can be in that moment and you don’t need to think about the overview because it’s all kind of there. Whilst you’re only focussing on one tiny detail, that bigger picture just sort of sits there in the background the whole time.

MJ: And I think if I was thinking about the bigger picture, I’d probably have a perpetual panic attack. You just deal one shot at a time. Denzil has the panic attacks.

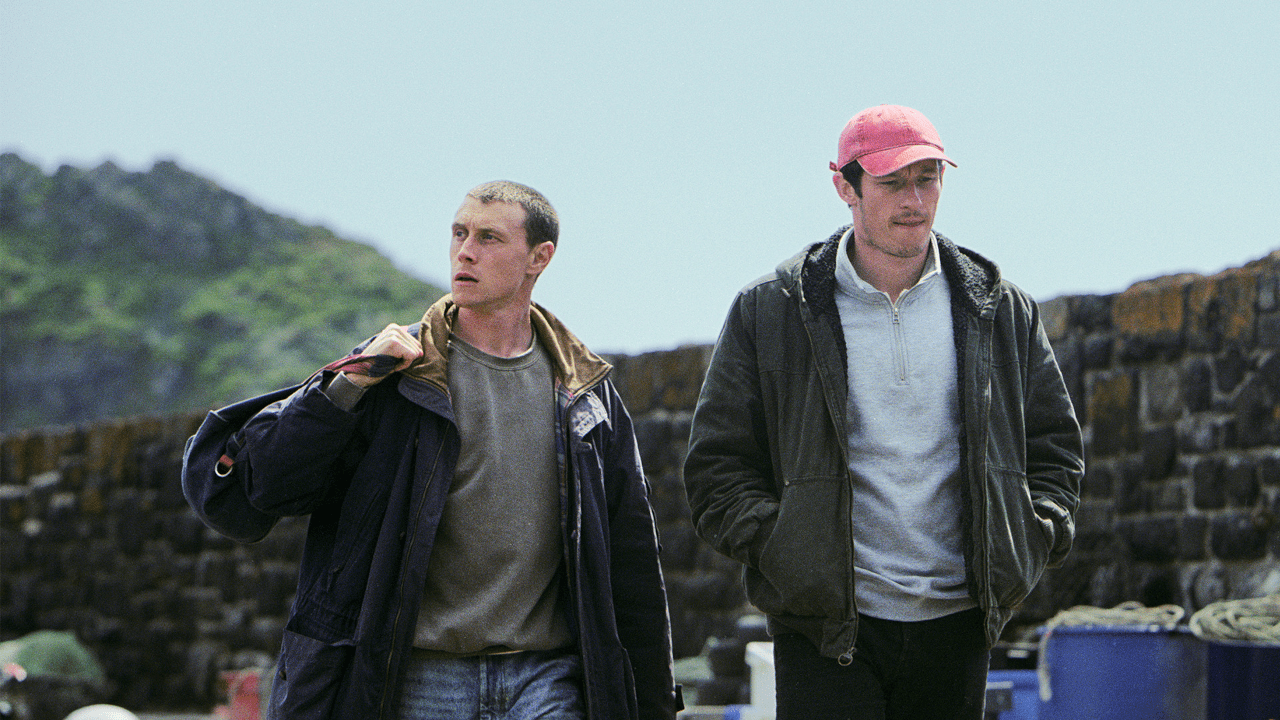

Film: Rose of Nevada

Director: Mark Jenkin

Genre: Drama, Fantasy, Horror, Sci-fi, Mystery

Stars: George MacKay, Callum Turner, Rosalind Eleazar

Run time: 1hr 54mins

Rated: TBC