Interview with director Ed Sayers founder of ‘Straight 8‘, who talks to the Language of Film about his feature film ‘Super Nature‘ at this year’s BFI London Film Festival 2025. Screening in UK cinemas from 2026.

Please introduce yourself and your film

My name is Ed Sayers, I’m a London based filmmaker and my film is ‘Super Nature‘.

What is the synopsis of your film?

The one I can do off pat is the log line: it is a love letter to nature created on Super 8 by people connecting across the world.

What is special about your film?

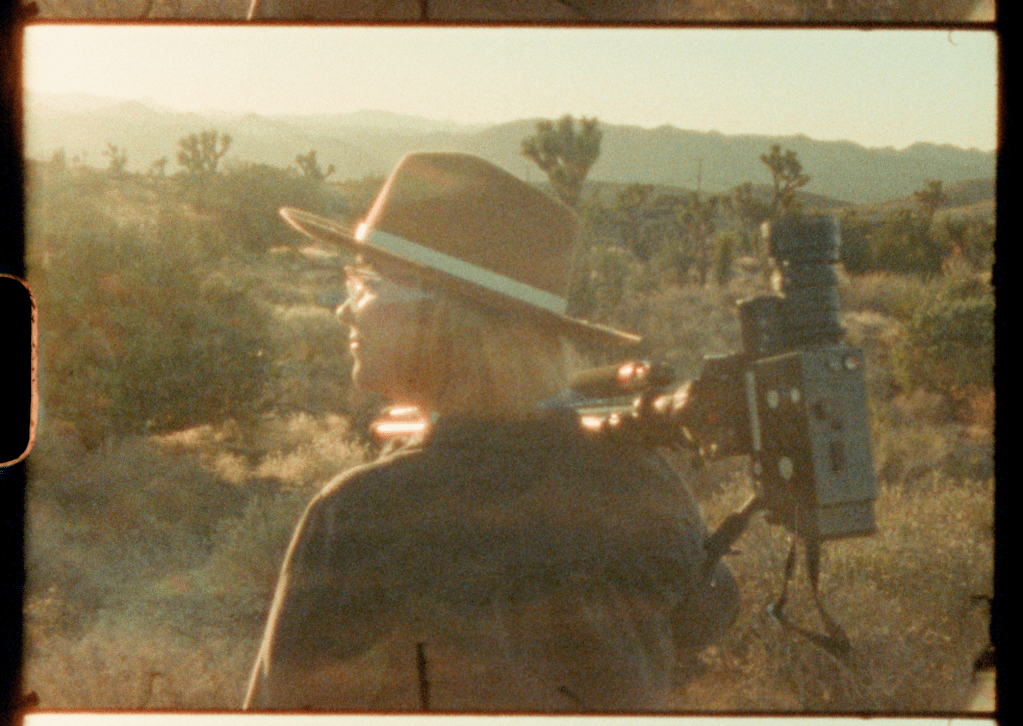

I’ll try and describe what you’ll be in for. I’d say it’s an 82 minute, full length feature doc. It’s an immersive adventure into our natural world via 40 filmmaking collaborators that I enlisted to help me try and capture the beauty of our connection with nature all on the medium of Super 8, the old fashioned home movie footage – the original home movie footage medium. I hope what it ends up being is a kind of snap shot of where we are in the world today, as human animals that are perhaps generally a little bit more disconnected from our brothers and sisters and environments more than we’d like to be or maybe ought to be.

Why make a nature film on Super Eight?

Good question, why would you make a nature film on Super 8 when you run out of film, it’s expensive and you can’t leave it running? It’s not the first choice for most wildlife filmmakers to shoot on antique film stock that runs out all the time!

I started a Super 8 filmmaking challenge inadvertently in 1999 when I asked 20 friends of mine that worked in film production to try something I’d been planning to try but hadn’t got round to. To make myself try this, I actually invited 20 friends to do it with me, which was to give ourselves a deadline, to give ourselves a roll of Super 8 film each and try and make a compelling short film on that one three-minute roll by taking a video, no retakes, editing with the camera, no grading, special effects, nothing. Making a separate soundtrack because Super 8 doesn’t record sound and the first time you see your work with its sound is at its public unveiling in a cinema!

That’s called ‘Straight 8‘ and for 26 years that’s been my sidekick baby and possibly master of my life. It was through that that I saw the power of Super 8 as a medium. I think it’s a very emotive medium and, 20 years into this weird experiment that grew out of control, we’d been receiving these wonderful one reel films from a French man in his 80s, who in his retirement from being a charcuterie butcher had become obsessed by filming insects and animals on Super 8 and is incredibly good at it. We’d seen film from him every year and he kept making our top selections and this one year he made this film that made our top selection and there was this moment in it that floored me every time and I couldn’t unpick why but it was having a really big effect on me. It is described in the film because it was the kick-off point to this project and all I knew was there was something in seeing nature recorded on this format that is nostalgic, and I think the ingredients of nostalgia are love and loss. I’m sure there is a cleverer academic who could make some sense of that but simplistically nostalgia is an emotion that embodies love and loss to me and I felt a hunch that we should record more of nature on Super 8. I started to talk to a few key people who I knew in the industry, one who was Asif Kapadia who was already on my jury for Straight 8 and another Jess Search, the late great Jess Search, who sadly died a few years ago, and they were both taken by the seed of the idea and gave me the confidence to try and push it forward.

Will a Super 8 film stand-up in modern cinemas today?

This is the amazing thing, in the early days of Straight 8 we used to project on Super 8. So we would find the projectionist with the most powerful Super 8 projector in the land, which is still not that powerful. As our audiences grew and grew, we got bigger and bigger cinemas. In fact we started in a 200 seat cinema in the very first one. The projector would be in the auditorium because if you kept it in the booth it didn’t have the throw but there was something very theatrical about having the smell and sound of the projector in the room. This was in the early days of Straight 8. Over time we progressed and we ended up, slightly reluctantly, moving towards digital projection.

Then Cinelab Film and Digital came on board and we started getting all our processing and scanning done there. They work on everything, they’ve just done the new Yorgos Lanthimos film, they work on Bonds, they do 65mm, 35mm, 16mm and Super 8 and they’ve been partners for me, both on Straight 8 and for this film, for a long time. We then started screening in NFT1 (BFI cinema room) for Straight 8 which looked glorious on a 4K DCP with Cinelab scans. Then we took it to the IMAX and the BFI testing it. They were into the idea but said let’s test it first because you might not like it or we might not like it. So we went to the IMAX and watched a 10 minute sequence of previous Super 8 films and we were all blown away by just a 10 minute set of clips. We were like holy shit. So, for the 25th anniversary of Straight 8, two years ago, we sold out the 500 seat BFI IMAX and showed the top 25 films on this format.

It’s a long answer to your question but what I’m basically saying is, I already knew and I was already making Super Nature by then and it was actually Asif Kapadia at that very first meeting, who was the one to say we need to record these animals whilst we’ve still got them and they should be celebrated on the largest screens in the land. This idea for this film should be on IMAX’s; and I was like whoa! So the short answer is yes, with an amazing scan of each Super 8 celluloid, which is smaller than your little finger nail, you can show it on the largest screen and it looks incredible. It’s just the beauty of that Super 8 grain only bigger than you’ve ever seen before.

Is it a filmmakers film because of its Super 8 format?

Yeah, but I hope it will go beyond that, I think it’s the obvious silos of audience, an obvious niche of audience, filmmakers and celluloid fans and nature lovers, but I hope that the film’s message, and I hope when you see it you’ll agree and certainly our world premiere last night and the messages I’m getting today, it speaks to our connection with the world. I don’t want the format conversations to get in the way of that. I think there’s something about the way the format is playing its part in translating that message about our crucial tether to what supports us and how delicate it is, that’s where Super 8 is important for me not for all the geeky stuff.

The film involves 40 directors from 25 different countries. How did your role work?

I’m the director, one of the producers and I was the editor and there was another editor that joined me for some of the editing journey, a brilliant editor called Dave Arthur who came on it for a couple of months as well. The way it would work is I started with people that I knew through the community of Super 8 filmmakers, that I already knew in different continents to talk to them about what might they film if they were to get involved and I started to quickly realise that I didn’t know that some of them had really deep connections to the Italian Alps or the weedy sea dragon in Tasmania. These were people I already knew who were not necessarily working in wildlife filmmaking and I didn’t know they had this nature connection. So, I didn’t do a public call out, I started off with people very organically but sometimes I was talking to someone I knew through Super 8 and then they asked me what else was I up to and I was like well I’m not really telling people about it, but I’m kind of working on this nature film and then suddenly two weeks later she was filming in the Italian Alps because I didn’t know her and her family had this massive connection to bringing the Ibex back to the whole valley where they disappeared from and her grandfather had reintroduced them. So I had a whole story there I would never have known about it if I hadn’t mentioned my secret project and then gradually the circles grew wider and Greenpeace got involved and started supporting us and opening up their amazing global address book of filmmakers and photographers and that brought about five people that contributed to the film and then they might recommend someone else that they knew in the global community. Sometimes, it was a couple going out in Patagonia in the search of whales and then they ended up getting amazing shots of baby octopuses because the whales wouldn’t collaborate or didn’t read the call sheet and didn’t turn up, you know! So it was a very organic way that the community grew, and it did grow into a community and so suddenly I had this new community a bit like the Straight 8 community. This new one of all these nutters going out to try and capture wildlife and the landscapes on this very tricky format on cameras that are 40-50 years old and often broke-down.

Did it make your job easier having all those collaborators?

Yes and no. I mean, I think when people talk about people’s superpowers and people say stuff to me and I’ve had a couple of people write to me having seen the film, and they’re like it’s community, like leaning into community. Like I said, I was planning to make a short film on Super 8 for over two years but didn’t get around to it but when I asked friends to join in I did it, like they did and I realised the power in working together, which is what we all need to do right now to save the messes we’re in, right? So to me, the finding the people and persuading them that this crazy endeavour might be something crazy enough to join me on, that came quite naturally. I think the biggest challenge was how do you stitch that into a story that someone other than that gang of people would really get something from. So stitching it all into a story was really hard and I’ve edited before but I’ve never edited a full-length feature film.

In the end we brought in a story consultant as well and that was amazing for me. I said to him last night you know, you were my sparring partner and my shrink and it really helped to have someone else there helping to sort of work out how we could choose some of the story beats because there were so many stories and backstories. I just started talking about how the project came about like we are now and we started getting post-it notes out again and rearranging the edit on the wall and that was a process. I’ve learnt so much from that and film is so malleable in the editing room. I mean, it is where the film is made. You could look at Fire of Love and The Fire Within, a Werner Herzog and another film about the same two people with the same footage but they’re completely different films. So I could have cut that film a million ways that was the biggest challenge. I edited all the people’s stories and I shared them back to them but they didn’t know the whole context of the film, we would just talk about it and maybe they would come up with a different change to their voiceover or something like that together. So it was quite collaborative but last night loads of those people saw the whole film and that was like a revelation.

Is the film a work of art or are you aiming to change the world?

Don’t rely on me to change the world or filmmakers and I wouldn’t like to call it a work of art because then it sounds exclusive and it sounds like we’ve all got to stroke our chins while we look at it. See it and let me know what you think. I hope that it’s a very accessible movie. It’s a great thing to see with other people because it’s all about togetherness not just of us but our other beings that we share a space with and that’s not just animals but the plants and the air we breathe and that’s what we need to be thinking about right now.